Feature w/Jordan Manley

Fall 2010, Issue 10.3

9 Pages, 2,726 Words

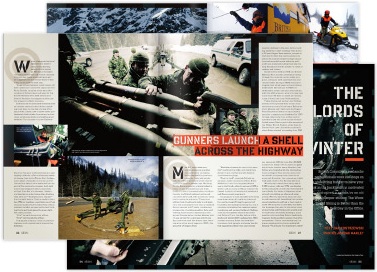

Jordan Manley pitched me on the idea of profiling three of British Columbia's avalanche professionals for this Skier piece. The window it provided into three very intense day jobs–from launching howitzers on Rogers Pass and ski cutting the Duffey Lake Road to heli bombing in remote logging camp fjords–made it one of my most memorable trips of all time.

Link to Full Story Online

“We are closing at this time,” squawks Eric Dafoe’s radio, as the flashing sweep vehicle passes us. We watch the lights roll onward up to the summit, where a backup of semis, tour busses and sled trucks will be clogging Canada’s million-dollar-a-day artery for at least the next hour.

“Rogers Pass Highway: west closure off, east closure on,” comes the reply from the Parks Canada complex at the summit, location of Dafoe’s desk and home base for the Glacier National Park ACS (Avalanche Control Section), the single biggest mobile avalanche control program in North America.

Dafoe works the five-day weekend shift as a senior avalanche technician, spending most days on skis but sharing office space with a busy crew of snow-smart professionals that include forecasters, technicians, safety specialists and a steady stream of visiting grad students.

Most BC skiers view avalanche science as a profession centered on recreation. But throughout the province a special fraternity exists outside of the powder-day framework of ski resorts and heli ops. Working for the government or private industry, these career avalanche professionals pry their trade in critical transportation corridors, heavily trafficked National Parks and remote Crown land with economic value to the resource economy.

These avy pros utilize their blasting tickets to mitigate risk, but also spend more than a hundred days a season in AT boots, constantly monitoring snowpacks, compulsively checking weather data and setting skintracks in spectacular ski zones. For a window into their day jobs, that read to us like dream jobs, photographer Jordan Manley and I set out on an avalanche road trip that started, where this work began way back in 1962, at the gauntlet of Rogers Pass.

“They’re hoaring stellars man! They’re classic hoaring stellars,” exclaims Scott Aitken, about as excited as a snow scientist could be about crystal structure. Aitken, is a BC Ministry of Transportation snow avalanche technician with 25 years working the Duffey Lake Road, the back route out of Whistler.

“Safety off, first fuse lit,” relays Rich Barry through the headset moments after he hoists the 25-kilo bag of explosive ANFO I hand him from my middle seat in the helicopter. Then, in accordance with Worksafe BC procedure, he yanks the double pull wire, igniting the two-and-a-half-minute fuse.

“First fuse lit, timer started,” responds his supervisor and private avalanche consultant Kevin Fogolin from the front seat, 7,000 feet above the deck. The machine is hovering somewhere above Brem River, a remote logging camp that consists of a lonely wooden doc, a one-lane road, a cab-less fuel truck and a decommissioned BC Ferry acting as a floating bunkhouse.

It’s a warm spring day in the Coast Mountains during Fogolin’s busiest season as, 2,000 meters below, logging operations are starting to heat up. But up here, in the definition of a costal alpine climate, far above saltwater fjords carving deep into glaciated peaks, the snowpack could be more than five meters deep-meaning the runouts down these near-vertical paths still threaten the valley floor.

“I think, like most avalanche people, it was the love of powder skiing and an element of self-preservation,” responds Fogolin, who rose through the ski-patrol ranks then took his levels through the CAA and CSGA. “But the thing with avalanches is it’s not like a lot of occupations where you go to university and get your degree and you become an avalanche guy. It’s the experience along with the training that provides you the opportunity to get into the field.”

And my opportunity to take the middle seat, next to the ANFO, arises after Manley captures shot one and shot two, and then is dropped on an unnamed peak for a better angle.

From our hovering vantage, we see the puff and then hear the “boom.” The cornice fails and the result propagates, two size-three slides ripping down each side of the arete. We fly in for a close-up, watching what seems like a raging waterfall down the path far below the skids.

“There she goes. That’s beautiful,” Fogolin says, as he watches with a combination of awe, excitement and respect shared only by big mountain skiers and avalanche professionals. “That’s a lot of snow.”

It’s an incredible sight of the destructive power that these mountains hold, as the slide unleashes a season of energy in its 1,400-meter tall, two-kilometer path to the edge of the dirt road. For the avy pros, the snowpack is a formidable adversary in a long campaign, but they’ve won this battle-at least for now.