Feature w/Grant Gunderson

October 2011, Volume 40.2

10 Pages, 3,437 Words

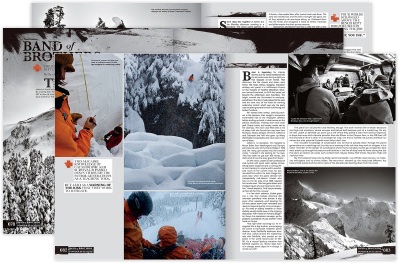

First slated for Skiing Grant Gunderson and I pulled this assignment after a major editorial shakeup at the magazine. We spent a second season tracking the patrol through their daily lives, from running control routes to hoisting pints, then created a feature for Powder that highlighted the brotherhood of the Baker patrol.

Link to Full Story

Thick flakes flew sideways as the coastal howl gusted to 80 mph, nearly blowing us off the chairlift. Mount Baker’s seven other chairs were done for the day, effectively shutting down access to Pan Dome from the White Salmon lodge below. But Chair Six was still spinning, delivering the few remaining skiers to fresh laps in the trees of North Face and Canuck’s Deluxe in yet another La Niña storm. By closing day, the 2010-11 winter would measure up as the deepest at Baker in a decade, with 857 inches of total snowfall. For now, we were still at the center of the storm in what had been a daily battle for the Mount Baker Ski Patrol to keep the ski area open and the public safe.

I’d been charging storm laps with Sam Llobet, Baker’s ski patrol director, who was still in uniform and still on the clock. Short, staccato bursts from Sam’s patrol radio blurted out dire predictions of four feet of snow, triple-digit winds and a near biblical meteorological catastrophe about to slam into the North Cascades. At this family area with world-famous terrain, the general manager on the other end of the radio had the ultimate power to shut it down, but Llobet’s calm, terse replies kept the area open for now. Maybe because the skiing was so good, maybe because, at 30 years old, he was one of the younger patrol directors in the West and maybe just because Mount Baker operates in its own vortex.

Since Llobet made the leap from parking lot crew to ski patrol at age 21, he has been part of the core group of hard-charging, hardworking skiers that keep careful watch over an area that received 565 feet of snow and logged more than 1.5 million skier days the last decade. It’s a massive job for the 14 skiers on the Mount Baker Ski Patrol, and creates a close bond between them—as they eat, work, drink, and ski together all season long. The lifestyle seems ideal, but the reality is that it takes a heavy toll—both mentally and physically—with success being measured in life and death.

The patrol isn’t all pitchers and whiskey, though. The work involves life-or-death decisions and high-risk situations, where success and failure both become part of a mental log. On any lift ride, Llobet or Sahlfeld can point out a cliff where they pulled a rider from serious exposure, a slope that once slid a female patroller from the Elbow to the Canyon fl oor, or the 125-foot cliff that claimed a life of a skier. It’s a strange trail map, one that is marked not just by unofficial run names but also potential hazards most skiers don’t see.

This macabre knowledge of catastrophe and survival is passed down through the patrol generations as a teaching tool, but also as a warning of the risk that they work to mitigate. It is a sober reminder of the danger of a profession where many everyday injuries go unreported, daily wear stacks up through the seasons and fatalities in the line of duty have hit home during the last five years at western ski areas such as Mammoth, Squaw Valley, Wolf Creek, Mountain High and Jackson Hole.

There is no big slide on Sunday. The 10-year, class-five, 16-foot fracture on Shuksan Arm comes the following day. It tears down over 1,000 vertical feet, filling Rumble Gully with 100 feet of debris, and covering fresh tracks from the morning. It is the largest slide Llobet or Sahlfeld have ever seen at Baker and it leaves everyone shaken.

Thankfully no one is killed. The consensus is that it was a very close call, avoided due to a combination of luck, policy and a timely, safe opening of Chair One that pulled the public away from the boundary. For Llobet, Sahlfeld and the Mount Baker Ski Patrol, it’s as close as they come to tragedy during this massive season. But they are still a long way from finished.

The collective sigh of relief will not come until the ceremonial bonfires, Metalmucil concert and ski patrol banquet on closing weekend 48 days later. But the fracture remains visible from Chair Eight as a reminder of both the danger and the debt this community owes to 14 skiers, who devote their winters to keeping the skiing public safe. It is a brotherhood unified by both responsibility and commitment—and it is why they wake and boot up before dawn and go to work.