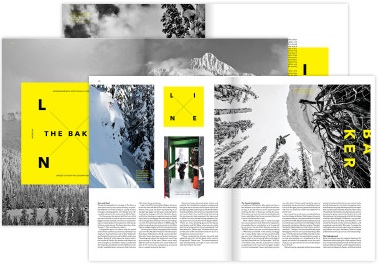

Feature w/Scott Sullivan

October 2012

10 Pages, 3,184 Words

Mt. Baker is very close to my heart. So writing a feature on the lineage of one of the sport's birthplaces for Transworld editor Gerhard Gross became a tougher task than I originally anticipated. But using the Legendary Banked Slalom as a frame, the feature story provided a window into the generations, influence and rootsy vibe of Mt. Baker.

Link to Full Story

Rain is hammering the blacktop on the Mt. Baker Highway and I am being pulled back again, one mile-marker at a time, to the heart of a storied Northwest community. The vortex at the end of this winding two-lane is the mossy hamlet of Glacier and its anti-resort of Mt. Baker, which has long represented something original, defiant and pure in a sport that has been heavily trending for three decades. As an icon, Mt. Baker is deeply woven into the lore and the history of snowboarding. But Baker is equally famous in the pro ranks as a grassroots breeding ground, spawning riders, rebellion, and style defined by big-mountain skill and a proudly maverick streak.

Like many Baker locals, I’ve been down this road hundreds of times before, chasing converging storms to the 1,500-foot, 1,000-acre ski area that will accumulate 808 inches of snow during the 2011/2012 winter. As a birthplace, it all began in the early ’80s, when longtime General Manager Duncan Howat granted Craig Kelly, Dan Donnelly, Carter Turk, Jeff Fulton, and the Mount Baker Hardcore (MBHC) access to his slow, diesel-powered Riblet double chairs at the edge of the North Cascades Wilderness. The scene that sprouted from those

roots has created a pro lineage intertwined with a mountain that now resonates with snowboarders worldwide—and not just for its steep terrain and massive accumulation.

Not all days at Baker are the same, and the February weekend of my arrival is the biggest draw of the season—Glacier is packed with pros who migrate here annually to compete for the most coveted roll of duct tape in snowboarding. At Mervin’s Method House party, local pros such as Matt Edgers and Forrest Burki mix with big-budget celebrities from Travis Rice to Mark Landvik over fish tacos in the kitchen. Muddy shoes pile up by the front door, medicinal smoke wafts from the balcony, and stiff drinks in red keg cups circle as musicians Scott Sullivan and Wes Makepeace play the living room to an eccentric crowd. Downstairs in the garage, the next pro hopefuls wax on and off with One Ball Jay as the Glacier mist continues its steady drip from the forested canopy.

It is a pre-race scene that has played out for more than two decades, but one where wave after wave of homegrown pros from Craig Kelly and Temple Cummins to Lucas Debari have backed up the Baker mystique by winning bragging rights against the biggest pros in the business. At the Method House, the party rolls on as riders who haven’t yet made the finals roll out early. After all, this is the Legendary Banked Slalom where skill trumps fame, and race day is taken almost as seriously as the freeriding.

The sky has cleared, but I am deep in The Cave—a snow cave next to the course—drinking a contraband Rainier on finals Sunday in a party of team managers, photographers, and Glacier locs’ with my deck stacked in the snow next to 20 Lib Techs.

On the course, the second and final run of the pro men’s division is now on tap, and a mix of the biggest names and best unknowns in snowboarding are rocketing down the serpentine, half-natural, half-man-made course. The heavy favorites—Terje, Temple, T. Rice—are about to drop in.

Baker has always been the regional epicenter for Northwest riders looking for a little support. But as pro snowboarding rediscovered its freeride roots and gravitated to deeper, under-hyped locations, riders such as Habenicht, Debari, and Mark Landvik earned their shots out of what had become a dead zone for exposure during the park-and-rail era. With the explosion in digital media, more crews started showing up to shoot lines and features. And especially during lean years in other locales, like last winter, Baker becomes a place to get a few shots and stack some footage.

Like many, Burki landed at Baker due to its terrain and its vibe. But with wins at the North Face Masters, he’s now filming, shooting, traveling, and working at solidifying a career as a pro freerider. It’s a tough niche compounded by factors like crew dynamics, Baker’s prevalence of stormy skies, and unforeseen problems like the smash-and-grab theft that resulted in the loss of his splitboard the night before my arrival.

For a freerider like Burki, shooting tree jibs on a powder day seems painful. Generations of other local chargers like Devenport, Cummins, and Edgers have long lost their powder-day patience for film crews, but Burki is still trying to earn his shot. “It’s not going to change that much,” Burki says. “The weather is gnarly, the snow is gnarly, the terrain is difficult to ride, and the mountain in itself regulates since there are only a certain type of people who can handle living up here.”

In the MBHC era of snowboarding, Baker was a bit of a secret. “We had utopia, dude,” original MBHC Dan Donnelly confirms. “I’m just glad that we were lucky enough to have the opportunity to have what we had, at that time, that golden era of unlimited powder. It’s similar to having Pipeline or Malibu in the early ’50s with you and your four buddies—it’s all there for the taking, just for you.”

But as riders from Jeff Fulton, Carter Turk, and Craig Kelly to Mike Ranquet, Jamie Lynn, and Tex Devenport gained respect and renown, the mountain started attracting wave after wave of attention and ridership. But no spike in traffic compares to the boom since 2005 that was sparked by a combination of new media exposure, the resurgence of freeride, and the rapidly growing population of neighboring Bellingham.

Now, unless you spend most of your time splitboarding—like Donnelly—scoring Baker without the side-slipping hordes is an almost unheard of experience. But three weeks later, I drop into a timewarp. An unpredicted spring storm has delivered a sneaker powder day, and the hill feels eerily empty. My silence is broken by the booming voice

of longtime 686 pro Pat McCarthy, heckling me from the chair. We link up at the entrance to the sidecountry, one slow-speed quad ride above the new Raven Hut Lodge.

“There were very fluid snowboarders coming out of Baker very early on.” Temple reflects. “But definitely the early acceptance of snowboarding started progression much quicker than other places even in Washington and around the country. People respond to that. Baker is known worldwide for the people who come out of it and the terrain equally. They are like mini generations.”

Sick lines and deep days blur together at Baker, but local riders mark the timeline of seasons by the LBS. Cummins shows up in most memories of the event. When the LBS times were tabulated for 2012, Habenicht won the friendly local wager, beating Debari by less than a second, stacking a fifth-place finish in the pro men’s division and avoiding a big-wall climbing trip for at least one more year. Adding to the lore, 37-year-old Terje Haakonsen took home his seventh LBS crown, slipping out to catch a flight to Norway before the duct tape was handed out at the White Salmon Lodge and the victory dinner raged late at Milano’s. Cummins slid smoothly into third, making yet another podium appearance. Then, like many of the elusive Baker riders, he disappeared again into the storms, leaving only tracks to follow for the remainder of the season. And, like all of them, he continued to make his mark on a mountain that has raised so many, so well, in its shadow.